Bifurcated. That’s the best single word I can think of describing how things seem to me right now. We’re in this strange period of emergence, where things are half locked-down; half exactly as they ever were.

My working time is now split 60:40 between remote working from home and the office. I’ve written a rota to get one engineer per day into the office for the next 6 weeks. Mini-pie is back in school 2 days a week. Next week I’m attending an actual, real, in-person, external meeting to kick off a new contract. I’ve just been to a book shop where I had to queue to get in and immediately use hand sanitiser upon entering, as directed by a staff member wearing a full plastic face shield. On my walk home, I saw crowds of people drinking beer in the sun, crammed in by the river.

So in this weird in-between phase I’ve found myself making some foundational changes to my approach to my work. There have been three broad areas of change:

• Task Management

• Equipment

• What’s on my Phone

Task Management - Bullet Journal No More

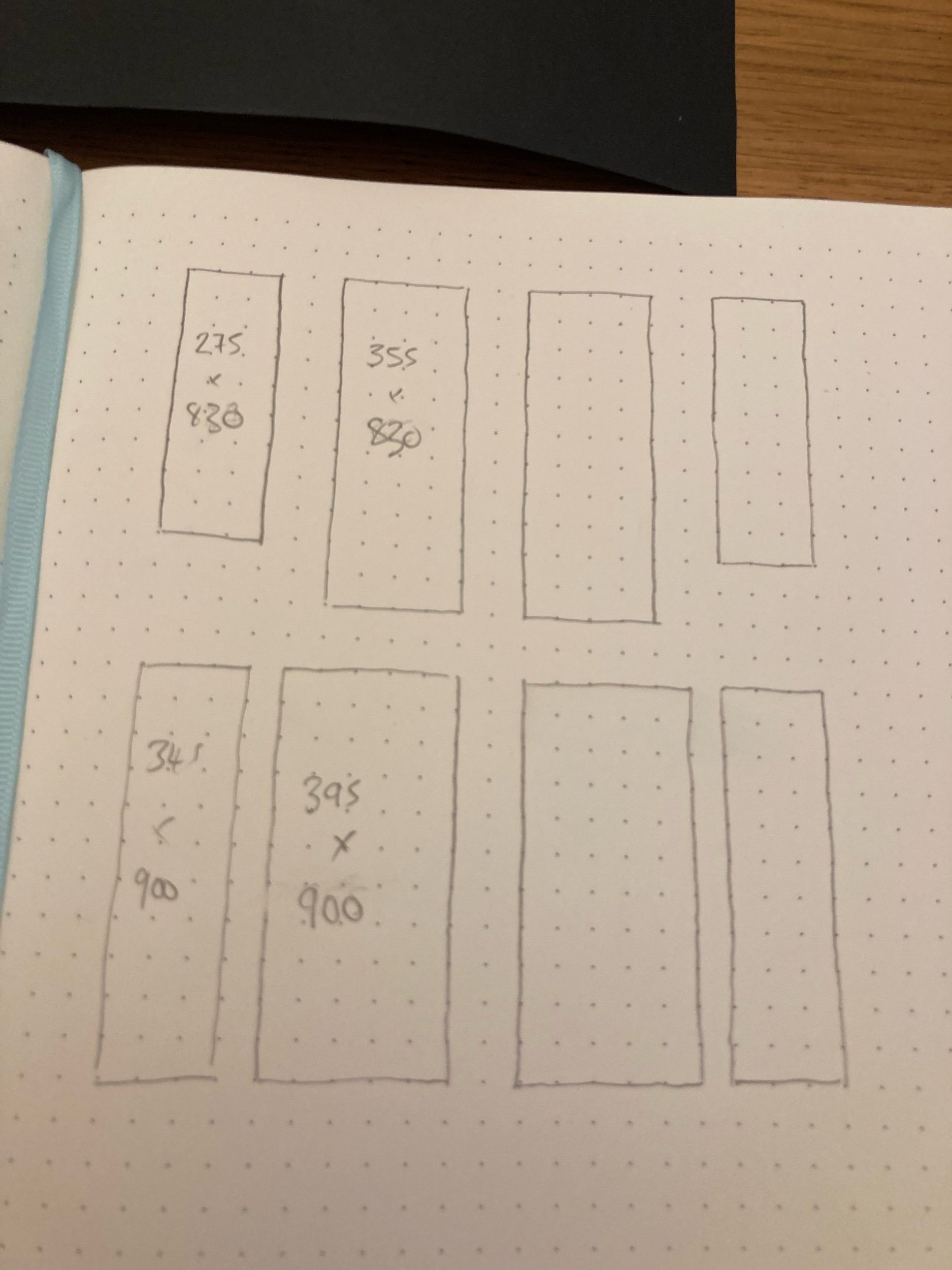

Since the start of the year, I’ve been using a physical bullet journal to track all of my tasks. Ever since I started using pen and paper, I knew that I was doing it out of sense of wanting to feel in control, but there was always a risk that the sheer amount of tasks I need to juggle would overwhelm the system. That point duly arrived in the middle of last week, when I started going over two pages, and I was losing the will to keep up with it.

Sorry pen and paper; it was nice while it lasted.

Back to GTD

Whenever I feel overwhelmed or feel I’ve got too many tasks to keep track of, I fall back on the Getting Things Done (GTD) method. This new disjointed life I’m leading lends itself to a more systematised life management scheme than ‘write a list of all the things I need to do in a book that I carry everywhere’, and GTD’s contexts are going to be especially helpful.

Previously, I used a bunch of Evernote hacks to create a GTD system, but Evernote’s pricing hikes pushed me off their system a couple of years ago. Luckily, an application called Notion has changed their pricing structure to be free to individual users with no limits.

Notion

Notion is difficult to describe in a few words, but for our purposes it can be thought of as something capable of creating a sort of personal website, and that website can have built in elements like databases. The really powerful feature that makes it useful for GTD is the ability to have linked databases. Conceptually, it’s like having a spreadsheet, where individual cells can also be spreadsheets.